The Case for Contradiction

INTRODUCTION

I don’t know what your specific interests are, but based on the ever increasing role of technology and digital media in our lives, I’m fairly confident making the following claims:

Regardless of how niche your interests are, the internet almost guarantees that…

There is more publicly available content / information than ever before

This information has never been easier to access

People are arguing about it

Said differently, our pool of information is becoming both larger and easier to access. As a result, we are more likely to come across ideas that contradict each other.

Though we may not always realize it, we have the power to choose how to engage with contradictions. Instead of allowing contradictions to create internal tension or feelings of anxiety, we can use them as a tool to improve our decision making and find balance in our lives.

We’ll explore this shift in mindset by discussing the following questions:

First - are we “allowed” to hold seemingly contradictory opinions?

If so, how can we use these perceived contradictions to our advantage?

GETTING COMFORTABLE WITH CONTRADICTIONS

Are we “allowed” to hold seemingly contradictory opinions?

Contradictions tend to be uncomfortable - they inherently involve some level of conflict or disagreement. Whether this sense of conflict is internal (e.g., choosing between your passion vs. a high paying career) or external (e.g., arguing with an uncle at Thanksgiving), we as people generally seek to resolve this tension however we can. If it’s an internal dilemma, we think through the issue and decide where we stand on it. If it’s an external conflict, we try to reach a compromise or agreement of some sort.

In other words, our preferred method for “resolving” a contradiction is to land on one side of it. While part of this inclination for decisiveness is likely instinctual, I’m also of the opinion that our culture (“business” culture in particular) tends to lionize a “bias for action” above all else. And action requires us to commit to a decision, again choosing one side over the other.

Silicon Valley tells us to move fast and break things. Biographies are written about leaders who make bold, instinctual decisions. When given two paths, rewards await those who choose the “correct” one and discard the other one (whether that reward is money, status, or power).

I am not here taking a position against the benefits of decisiveness. I recognize that in many contexts, we must commit to a decision and discard the other option.

The idea I’m putting forth today is one that I believe can serve as a valuable input to decisiveness, an approach we can use to feel more comfortable and confident in our decisions. It’s an idea that applies to all of our decisions, whether they’re being made in a boardroom or in the everyday moments of our lives.

This entire notion started with a single quote:

“The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” - F. Scott Fitzgerald

However, this idea relies on the following premise: not only are we allowed to hold seemingly opposed ideas as valid, there are often many situations where holding contradictory opinions as valid is advantageous.

To build on this concept and take it a step further, I’d actually posit the following as a guiding principle: the more abstract a situation is, the more value there is in holding contradictory viewpoints as valid.

In the section below, I’ll explain how contradictions can be of value. Right when things get a little bit too abstract, we’ll also take a look at some practical examples to keep us grounded:

Being grateful, yet ambitious

Getting motivated vs. staying disciplined

Finding the long view on a “short” life

Taking work seriously without taking yourself too seriously

Balancing mindfulness with mind wandering

However, since I took the liberty of establishing a principle up above, I feel obligated to qualify the hell out of it. Keep the following disclaimers in mind:

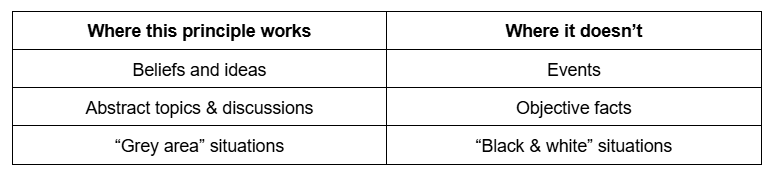

Disclaimer #1: This concept generally works well with…

Beliefs and ideas (as opposed to events)

Abstract topics / discussions (as opposed to objective facts)

“Grey area” situations as (opposed to “black and white” situations)

In other words: use this principle to make informed decisions, not validate delusion.

A quick example:

In 2014, Macklemore’s “The Heist” won the Grammy for Best Rap Album. This is an event that already happened - it’s an objective fact. Consequently, there’s little value in assessing contradictory viewpoints that say otherwise.

However, if I were to tell you that Kendrick Lamar’s “good kid M.a.a.D city” should’ve won, that’s a belief and idea. There may be some value to be had in assessing each of those contradictory viewpoints before you make up your mind.

Disclaimer #2: It’s less important that the ideas you’re debating are truly complete opposites or contradictions. They only need to be perceived as incongruent for this to be useful.

Example: Gratitude and ambition are not diametrically opposed traits. However they tend to have conflicting connotations that can make them feel at odds with one another

FINDING VALUE IN CONTRADICTIONS

How can we use perceived contradictions to our advantage?

Now that I’ve hedged and caveated to my heart’s content, let’s dive into the value we can derive from holding contradictory viewpoints as valid. As I see it, there are two ways this principle helps us shift from a mindset where contradictions cause anxiety to one where contradictions can improve decision making:

1) Maximizing your pool of information: As we discussed in the first section - when faced with opposing ideas, we tend to favor one while dismissing the other, limiting our engagement with the opposing viewpoint. If we think of a collective body of knowledge and experience as a “pool of wisdom”, prematurely choosing one side or the other essentially cuts this pool of wisdom in half.

Rather than invalidating an idea, we can recognize it as valid but not always applicable. This approach maximizes our 'pool of wisdom,' allowing us to draw from both perspectives as needed. The focus then shifts to determining when one idea holds true over the other.

In situations where a practical decision must be made, this principle insinuates that there is actually a “decision before the decision.” We should choose to genuinely engage with both sides of a contradiction before formalizing our position or choosing our path forward.

2) Creating a spectrum of possibilities (to find balance): As we discussed above, when we hold contradictory ideas as valid, our focus then shifts to identifying when one idea holds true over another. However, something else cool happens - we also create a range of possibilities between these two end points. In other words, we create a spectrum. Instead of thinking in black and white, we start to see all the shades of grey.

With a wider range of possibilities now on the table, we have more flexibility to determine where on a given spectrum we think we should be in a given situation. Holding both ends of the spectrum as valid allows us to lean more to one side or the other depending on the situation at hand.

Thinking in these terms ultimately helps us drive towards a more balanced, fulfilling life.

EXAMPLEs

I recognize that the value discussion above was very abstract. To help clarify what the hell I’m talking about, we’re going to take a look at some examples of specific contradictions that this principle has personally helped me reconcile.

Since these examples are from my own experience, they’re going to lean a bit self-helpy. If they resonate with you, that’s great. At the very least, I hope they serve as initial guideposts for whatever contradictions may be more applicable to your specific situation.

Being grateful, yet ambitious

Although gratitude and ambition are not directly contradictory, the connotations around each word often make them feel at odds with one another. In my experience, it’s pretty easy to feel ambitious at work and grateful at church. However, switching those contexts would probably feel a little bit awkward.

This principle allows us to get comfortable with the fact that you can be grateful for everything you have in the present moment, while also having a desire to continue progressing or achieve future goals.

When you feel like you may be stagnating or in a “velvet rut” (i.e., in a comfortable situation, but not actively growing), these may be signals to slide down this spectrum of contradiction and lean into your ambitious side.

On the contrary, if you’re feeling stressed or burned out, you always have the option of leaning further towards the gratitude side of the spectrum.

Getting motivated vs. staying disciplined

Motivational speakers will get you jazzed up and ready to run through a wall. Navy seal podcasters will denounce motivation as a fleeting source of energy only needed by the weak. From their seat, discipline is obviously the path to results.

As usual, reality tends to be somewhere in the middle. Motivation helps us start things, and discipline tends to keep us going.

If you’ve been incredibly disciplined and regimented on your 5x per week fitness plan and you’re feeling burnt out one evening, maybe it makes sense to slide away from the discipline end of the spectrum a little bit. Give yourself grace and avoid burnout.

However, if you’ve been “avoiding burnout” for 3 weeks and can’t remember if your gym membership is still active or not, maybe it’s time to lean a bit more towards the discipline end of the spectrum. In these scenarios, it’s often helpful to reconnect with whatever motivated you in the first place.

Finding the long view on a “short” life

I’ve heard people older than me tell me that the days are long, but the years are short. Now that I’m sniffing 30, I tend to believe them. However, it feels like the overwhelming popularity of the “life is short” mantra has created so much urgency that if we’re not firmly established in our careers by 25 then we feel inherently flawed.

Life is by definition the longest thing we do, it makes sense to think of it more like a marathon than a sprint sometimes (or perhaps, a lot of the time). Yes, urgency is needed sometimes, but you don’t have to become everything you’re ever going to be overnight.

“Life is short” is a great mantra to drive urgency and encourage action, but we’d be wise to consider the other end of the spectrum more often. Life is also long - you need to pace yourself sustainably. Acknowledge the reality of trade offs. You can’t be everywhere at once.

Taking work seriously without taking yourself too seriously

It’s ok to approach a serious topic or meaningful work with a sense of humor. You don’t have to be stern or “serious” all the time to demonstrate your competence or commitment to a cause.

Yes, there are plenty of times when you need to bear down and burn the midnight oil. These periods, when things seem particularly bleak and exhausting, often serve as prime opportunities to re-energize a team by injecting some levity into the situation.

(Note: For more on this one, I’d point anyone interested to the book “Humor, Seriously” by Jennifer Aaker & Naomi Bagdonas)

Balancing mindfulness with mind wandering

Mindfulness and mind wandering tend to be at odds with one another, but both have been found to have their own benefits.

Mindfulness calls for a concerted, focused effort to remain in the present moment. It’s been shown to improve our ability to focus, help us regulate our emotions, and foster a sense of clarity and relaxation.

On the contrary, letting our mind wander with little to no structure has also been shown to produce its own set of positive benefits. Unstructured time enables our brain to make unexpected connections, allows our subconscious to work through thoughts and emotions, and often leads to “aha!” moments and new insights.

Being mindful and intentionally focused on the present moment is a great way to appreciate the little things in daily life. However, if we’re always focused on the present moment, there’s no time for our minds to wander, play, and form unique connections and creative ideas.

When your mind is all over the place and things feel completely chaotic, use mindfulness to bring yourself back to the present moment and focus your thinking. But also be intentional about carving out time to allow your mind to wander - it often feels like all of the best ideas come when we’re not looking for them.

Hopefully these examples are helpful - if not, I’m sure there are a thousand other seemingly contradictory ideas that may be more applicable to your situation. Either way, hopefully the core tenets resonate:

Think twice before invalidating an idea that seems contradictory - try to maximize your “pool of wisdom” when possible

Think of contradictions as the ends of a spectrum - move yourself on this spectrum until you find your own sense of balance (this is a “feel” thing, and will vary from person to person)

CONCLUSION

By applying these core tenets and getting comfortable with holding contradictory ideas as valid, we can improve our decision making and (hopefully) drive towards a more balanced, satisfying life.

Unfortunately, we don’t build this muscle by sitting around and reading essays like this. We start with an instinctual feel or pull in one direction, and ultimately feel our way through everything the world throws at us. In other words, we all learn for ourselves by trial and error.

My hope is at the very least, the concepts covered here give you a new lens into how to think about and navigate the ongoing process of trial and error in your own life.

Thank you to Nikiel Kim, Thomas Kreiling, and Nick Foster for reading various versions of this essay.